Cockpit has now been in Debian unstable and Ubuntu 17.04 and devel, which means it’s now a simple

$ sudo apt install cockpit

away for you to try and use. This metapackage pulls in the most common plugins, which are currently NetworkManager and udisks/storaged. If you want/need, you can also install cockpit-docker (if you grab docker.io from jessie-backports or use Ubuntu) or cockpit-machines to administer VMs through libvirt. Cockpit upstream also has a rather comprehensive Kubernetes/Openstack plugin, but this isn’t currently packaged for Debian/Ubuntu as kubernetes itself is not yet in Debian testing or Ubuntu.

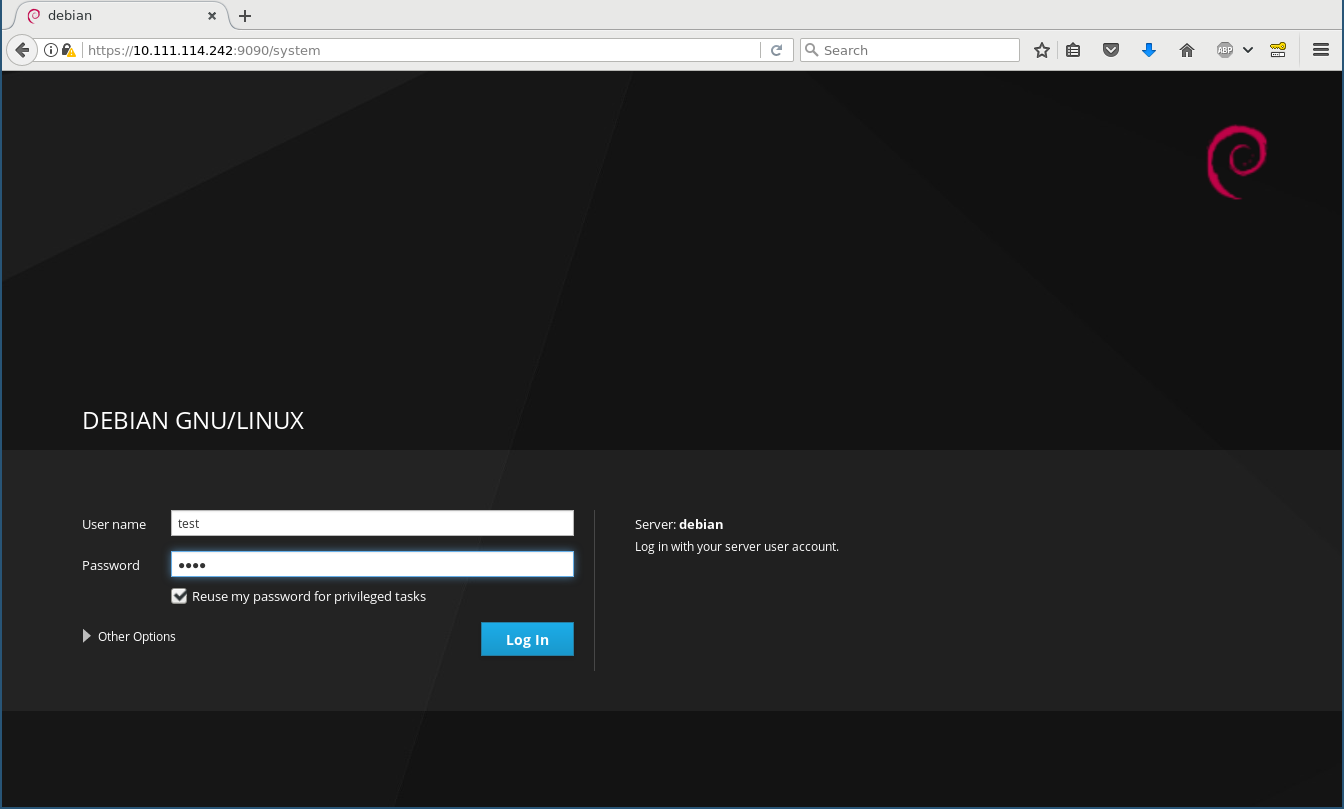

After that, point your browser to https://localhost:9090 (or the host name/IP where you installed it) and off you go.

What is Cockpit?

Think of it as an equivalent of a desktop (like GNOME or KDE) for configuring, maintaining, and interacting with servers. It is a web service that lets you log into your local or a remote (through ssh) machine using normal credentials (PAM user/password or SSH keys) and then starts a normal login session just as gdm, ssh, or the classic VT logins would.

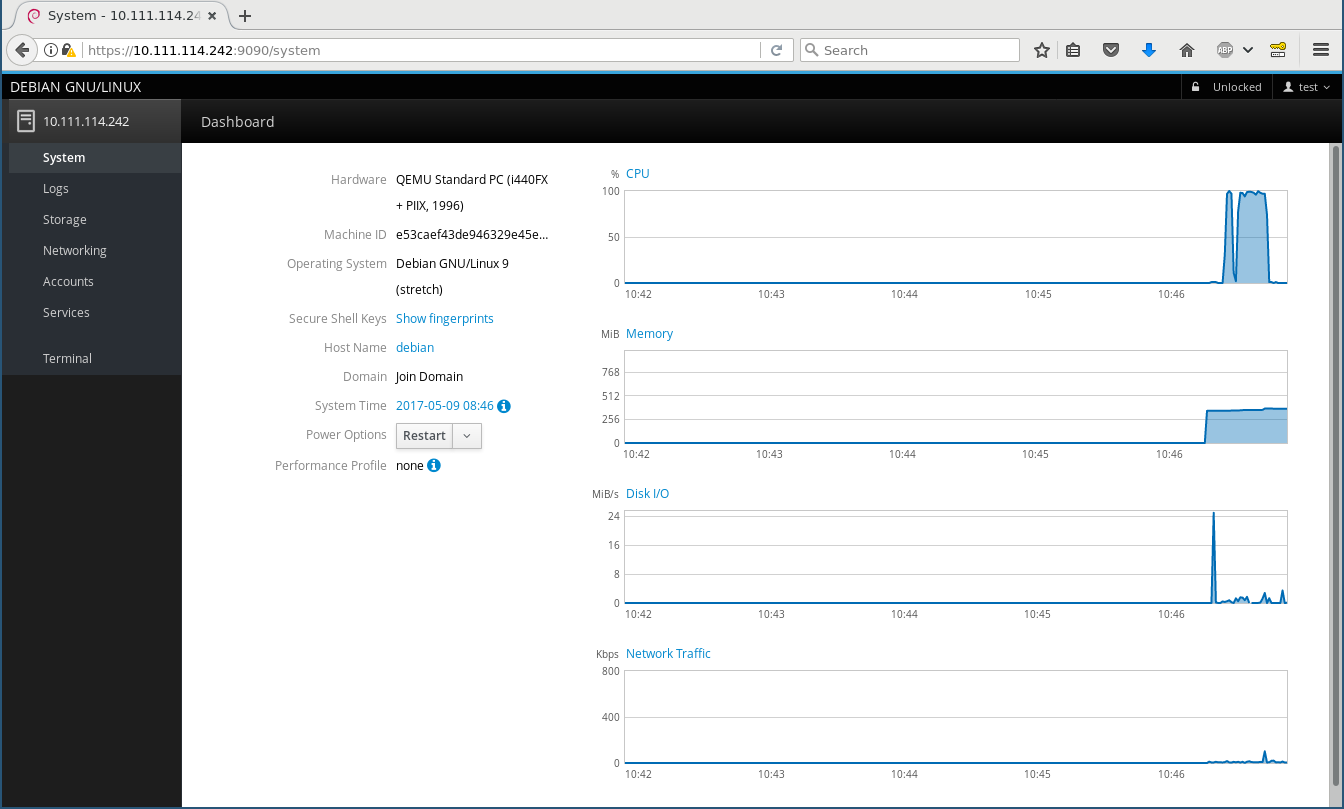

The left side bar is the equivalent of a “task switcher”, and the “applications” (i. e. modules for administering various aspects of your server) are run in parallel.

The main idea of Cockpit is that it should not behave “special” in any way - it does not have any

specific configuration files or state keeping and uses the same Operating System APIs and privileges like you would on the command line

(such as lvmconfig, the org.freedesktop.UDisks2 D-Bus interface, reading/writing the native config files, and using sudo when

necessary). You can simultaneously change stuff in Cockpit and in a shell, and Cockpit will instantly react to changes in the OS, e. g. if

you create a new LVM PV or a network device gets added. This makes it fundamentally different to projects like

webmin or ebox, which basically own your computer once you use them the first

time.

It is an interface for your operating system, which even reflects in the branding: as you see above, this is Debian (or Ubuntu, or Fedora, or wherever you run it on), not “Cockpit”.

Remote machines

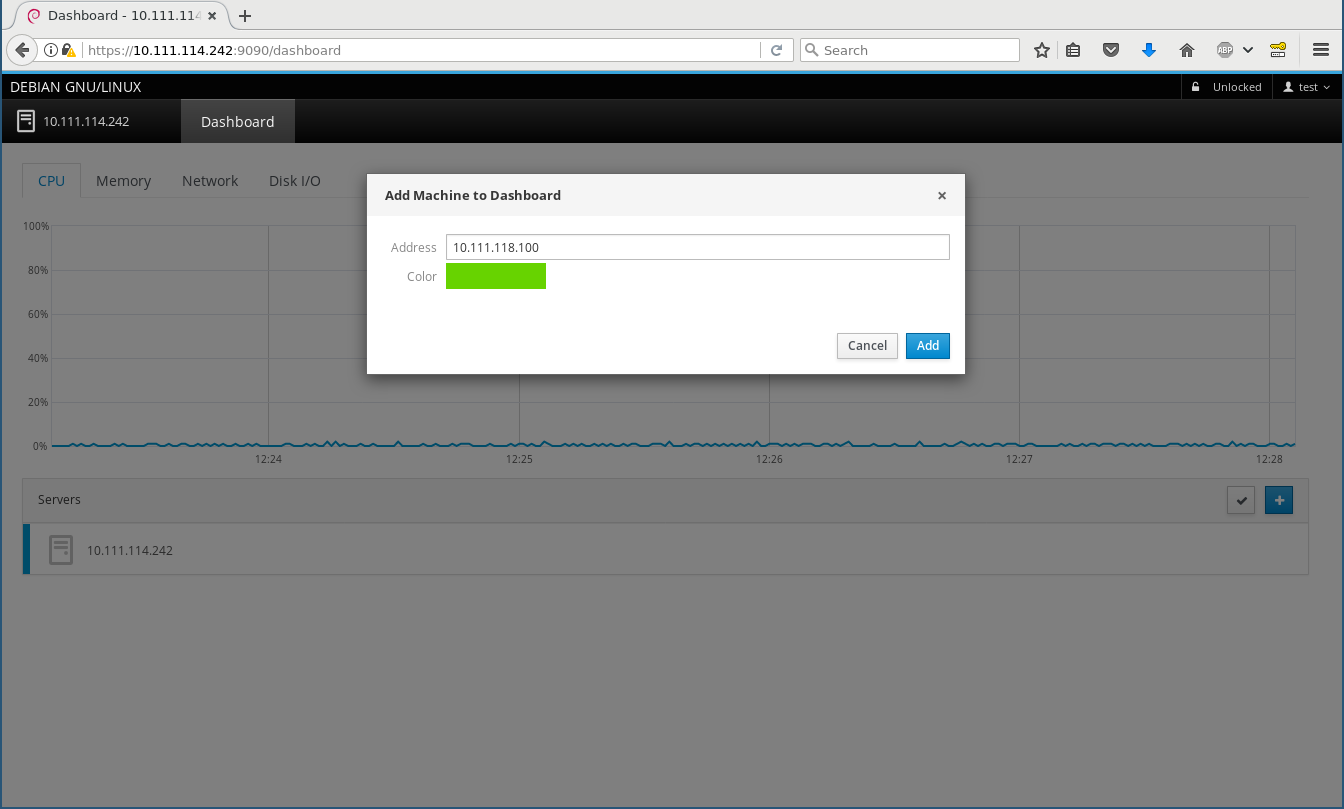

In your home or small office you often have more than one machine to maintain. You can install cockpit-bridge and cockpit-system on

those for the most basic functionality, configure SSH on them, and then add them on the Dashboard (I add a Fedora 26 machine

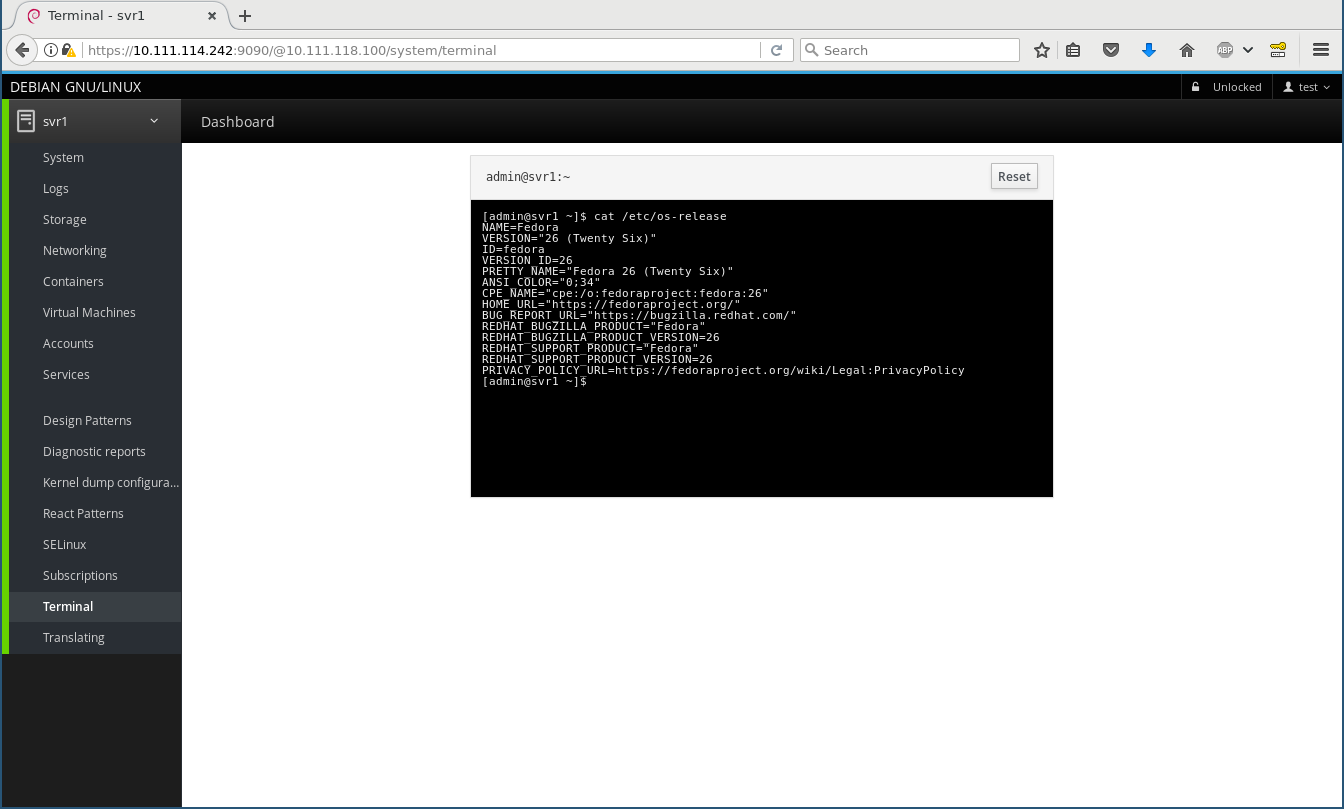

here) and from then on can switch between them on the top left, and everything works and feels exactly the same, including using the

terminal widget:

The Fedora 26 machine has some more Cockpit modules installed, including a lot of “playground” ones, thus you see a lot more menu entries there.

Under the hood

Beneath the fancy Patternfly/React/JavaScript user interface is the Cockpit API and protocol, which particularly fascinates me as a developer as that is what makes Cockpit so generic, reactive, and extensible. This API connects the worlds of the web, which speaks IPs and host names, ports, and JSON, to the “local host only” world of operating systems which speak D-Bus, command line programs, configuration files, and even use fancy techniques like passing file descriptors through Unix sockets. In an ideal world, all Operating System APIs would be remotable by themselves, but they aren’t.

This is where the “cockpit bridge” comes into play. It is a JSON (i. e. ASCII text) stream protocol that can control arbitrarily many “channels” to the target machine for reading, writing, and getting notifications. There are channel types for running programs, making D-Bus calls, reading/writing files, getting notified about file changes, and so on. Of course every channel can also act on a remote machine.

One can play with this protocol directly. E. g. this opens a (local) D-Bus channel named “d1” and gets a property from systemd’s hostnamed:

$ cockpit-bridge --interact=---

{ "command": "open", "channel": "d1", "payload": "dbus-json3", "name": "org.freedesktop.hostname1" }

---

d1

{ "call": [ "/org/freedesktop/hostname1", "org.freedesktop.DBus.Properties", "Get",

[ "org.freedesktop.hostname1", "StaticHostname" ] ],

"id": "hostname-prop" }

---

and it will reply with something like

d1

{"reply":[[{"t":"s","v":"donald"}]],"id":"hostname-prop"}

---

(“donald” is my laptop’s name). By adding additional parameters like host and passing credentials these can also be run remotely through

logging in via ssh and running cockpit-bridge on the remote host.

Stef Walter explains this in detail in a blog post about Web Access to System APIs. Of course Cockpit plugins (both internal and third-party) don’t directly speak this, but use a nice JavaScript API.

As a simple example how to create your own Cockpit plugin that uses this API you can look at my schroot plugin proof of concept which I hacked together at DevConf.cz in about an hour during the Cockpit workshop. Note that I never before wrote any JavaScript and I didn’t put any effort into design whatsoever, but it does work ☺.

Next steps

Cockpit aims at servers and getting third-party plugins for talking to your favourite part of the system, which means we really want it to be available in Debian testing and stable, and Ubuntu LTS. Our CI runs integration tests on all of these, so each and every change that goes in is certified to work on Debian 8 (jessie) and Ubuntu 16.04 LTS, for example. But I’d like to replace the external PPA/repository on the Install instructions with just “it’s readily available in -backports”!

Unfortunately there’s some procedural blockers there, the Ubuntu backport request suffers from understaffing, and the Debian stable backport is blocked on getting it in to testing first, which in turn is blocked by the freeze. I will soon ask for a freeze exception into testing, after all it’s just about zero risk - it’s a new leaf package in testing.

Have fun playing around with it, and please report bugs!

Feel free to discuss and ask questions on the Google+ post.